“I don’t feel at all ready for this trip. I don’t know how to work the Garmin. I hate the rain. I can’t repair a puncture. I feel unfit and useless!”

I am looking for someone to agree with me that this is a mad, stupid idea that can only end in disaster and should be stopped immediately. The day before I am due to leave, I want a way out.

Job done, I think, as I press ‘send’ on Whatsapp to my ex-husband. I sit back and comfort myself with sensible self-talk. I’m not Dervla Murphy, I can’t do it just because she did. I’ll be a normal person, get a job, and watch the rain and wind from the comfort of my own warm home instead of trying to cycle in it like a lunatic.

My phone lights up with the reply.

“It’s weird – I’ve not even considered the possibility of you not making it/bailing. Just feels like a certainty that you’ll make it because you’ve decided to do it.”

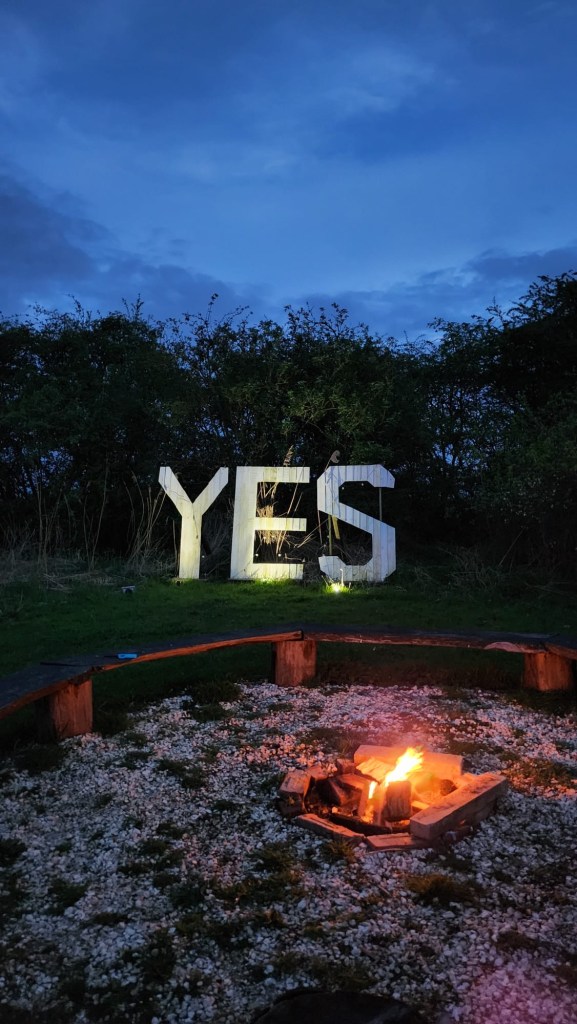

Shit. Guess I’m going, then.

Perhaps for the first time in my life, I’ve voluntarily started something that I genuinely don’t know if I’m capable of finishing. And that has made me more scared than I can remember ever being before. It feels as if I’ve been stripped of an invisible protective layer of insulation against the caprice of the universe and found myself suddenly exposed and vulnerable.

I’ve been scared of cycling in the rain, being cold, lonely, stranded or lost, of hills, dogs, camping, leaving the UK, breaking my body or my bike, missing my children too much. My mind – normally agile – became immobilised by fear, even as my body – normally sedentary – powered me across the entire country. This is why it has taken me a few weeks to write my first blog post from the road.

I think this reflects the enormity of the challenge I’ve taken on. Forget Istanbul; I didn’t even know if I could make it to the end of the first day. “You look traumatised!”, said my friend Seonaid as she opened her front door to me standing there at the end of a very long and cold day of cycling from Glasgow to Haddington. And, though I was smiling, I felt it.

It took me 12 hours and a LOT of sugar, but I did make it. And, slowly, my other fears are being realised and overcome. I worked out how to use the Garmin and to stop it beeping at me, navigated ferries, survived lashing rain and headwinds and made it up some hills. And I’m learning that on the other side of fear is…the next fear to face, but also growing confidence.

Facing fears is hard work, and there has been less time for reflection than I imagined there would be. Each day, it takes an effort to get on the bike, work out where I’m going and where I’m going to sleep. I’m consumed by finding the energy to move, navigating, getting myself up hills or around other people, avoiding potholes, eating, drinking, checking the map. I repeat the same actions endlessly: change gear, brake, put hood up, reach for water bottle, drink, adjust garmin holder, reach back to check panniers are still there, indicate, pedal pedal pedal.

I remind myself that life is also much simpler this way. Each day is the same – eat, cycle, eat, cycle, eat, cycle, shower, eat, send a few messages on my phone, sort out my stuff, sleep. I don’t have to choose what to wear or what to do. I’m not required to attend any pointless meetings. I don’t do any housework. I’m outdoors all day. I remind myself to be present, to observe, be grateful, to enjoy it – this is what I dreamed about. This is a kind of freedom.

I still feel too close to the UK leg of my journey to really see it and reflect on it properly, like one of those pixelated pieces of art that you need some distance from for it to come together into a coherent image. At this proximity, there are some moments that stand out clearly.

Coming down the steep hill into Sandsend, listening to the wet wheels slipping against brakes that I’m squeezing tightly with gloved hands, I’m aware of a car behind me. The driver is a bit too close: he wants to let me know I’m in his way, even if he doesn’t want to risk overtaking me just yet. Rain and wind lash my face, but I don’t dare lift my hands from the handlebars to wipe the water away from my eyes: if only there were windscreen wipers for cyclists, I think fleetingly. Blink blink blink – see a huge, drowned pothole at the last second, swerve to avoid it, hear the car behind me follow suit. That could have been the end, I think, death by pothole, what a way to go. There is no refuge from the fury of this storm until the bottom of the hill, nowhere to stop and nothing to do but keep going. My senses are all on edge. This is mad, just wild, I think, and I smile despite myself with the exhilaration of it. I reach the bottom soaked, freezing and exhausted. In the bus shelter, eating my cold lunch of leftover rice and chilli as fast as I can, I listen to the muttering of walkers around me as they consult the forecast on their phones: 100%…next two hours…rain it says…100%…We all call it a day.

The expression on the face of a lady in Whitley Bay who didn’t stop at a zebra crossing that I was halfway across, nearly knocking me over in the process, has seared itself into my brain. She wasn’t looking at me, but I could read it: I’m not stopping, not me, not for her, no. Something in the set of her face, the rigidity of it, its implacability, chilled me (even more than the mighty wind of Storm Kathleen already had). I had offended her just by being on that zebra crossing with a bike. In an instant, she took against me. Or maybe it was the very idea of sharing the road that she objected to. She had the comfort and safety of a car; I was being thrown about by the wind, but she wouldn’t stop. Something about this took me back to the struggle of my teaching days; the mountains that had to be climbed to get some people onside. That moment tainted the whole of the UK leg.

I can still hear the creepy dripping of the long, dark tunnel along the Union Canal just after the Falkirk Wheel. Pushing my bike while slipping and sliding along the wet cobblestones, slimy wall on one side, unfenced dirty water on the other, passing strangers with hoods up and heads down, I felt like I could have been murdered at any moment and thrown straight into the canal, never to be seen again. I think: why don’t they light it? How has our country come to this?

And then the beautiful moments that I feel blessed to have seen. Turning a corner to see two rows of trees in dappled sunlight lining the path; catching the flash of bluebell woods out of the corner of my eye as I pedal past; witnessing a heron taking off across the canal in response to the approach of the bike; moving between fields of golden oil seed rape, waving to an elderly couple gardening together and chatting away. Each nod and smile exchanged with another cyclist or walker feels special. When a piece of music I’m listening to perfectly matches my mood and the moment and I punch the air with delight as I fly along the path alone, I feel glad to be alive in this place and at this time.

When I think about what helped me overcome the many fears I had about the UK leg of the journey, more than anything else, the warmth, kindness and love shown by people I know and complete strangers has touched me deeply and kept me going. People have fed me homemade cookies and delicious saag paneer, made me tea and packed lunches, offered to drive hundreds of miles to get me or book me a hotel at a moment’s notice if I get stuck, welcomed me into their home and introduced me to their children, washed my clothes, lent me equipment, sent messages of encouragement and words of wisdom, cheered me on, checked in, and smiled at me as I cycled past – every bit of it has been more important than I could have predicted before I started this journey. Life on the road is more raw than life at home. Every emotion is amplified. As the journey has progressed, it’s been lovely to recognise that it’s not only fear that is heightened, but also the impact of each small or big act of kindness. I’m so grateful for each of them.

In some important ways, the support of this invisible peloton (to borrow a phrase from Emily Chappell) makes me feel like I’m not all alone out there, and that gives me great comfort. Yet, in its essence, my journey is in truth a solo one. I’ve wondered, in the more difficult moments, whether this was the right choice. Then I remembered that this wasn’t the choice I had to make. My choice is either to go solo or not to go at all. And going I certainly am. Onwards!

One response to “To the end of Britain”

Great post, Sahir. Can’t wait to read the next one!

LikeLike